The ERA: A New Foundation for Equality in the United States

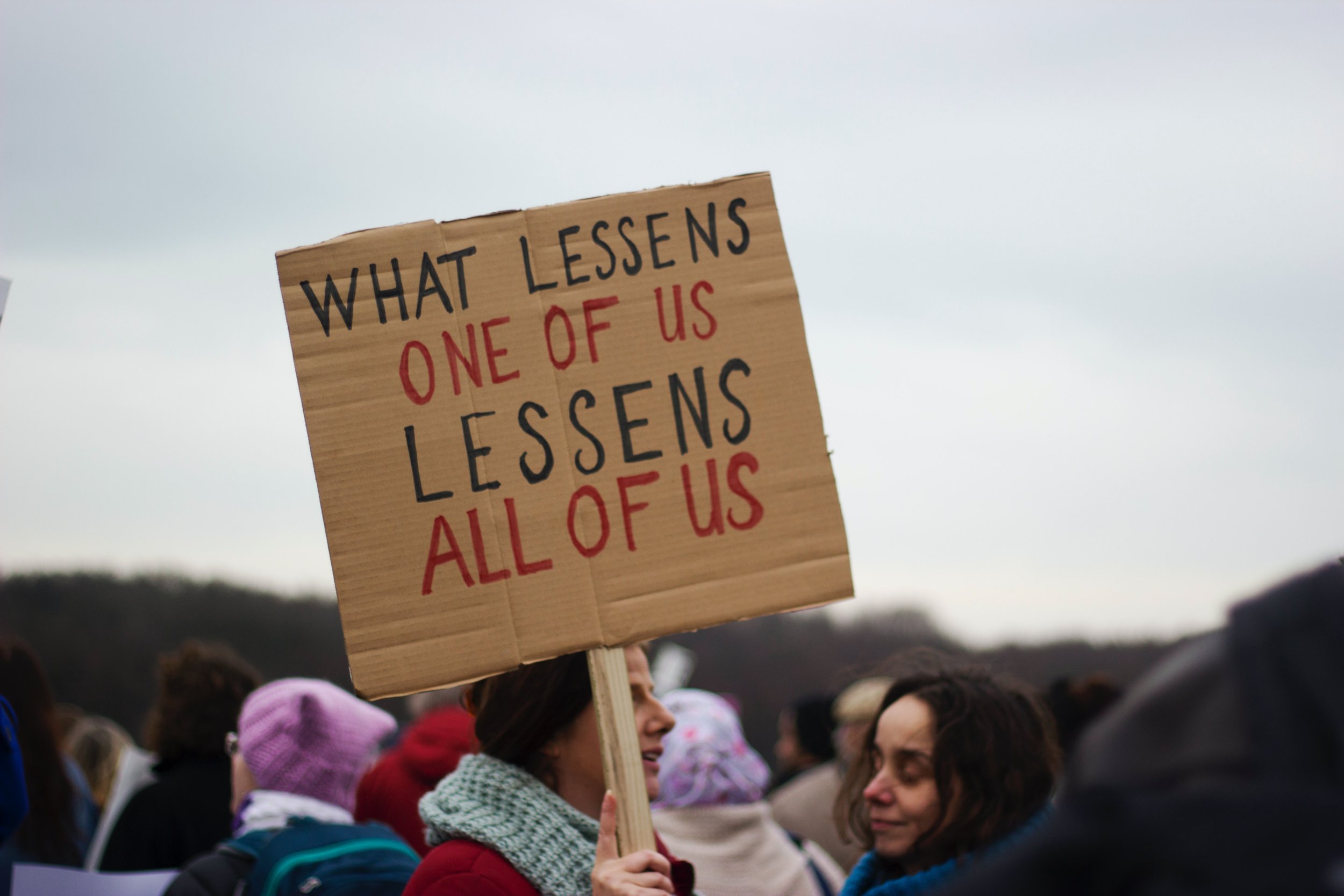

American democracy is an unfinished project. Our nation was founded on principles of equality and justice for all, but living up to these foundational principles is the animating challenge of our history.

In 21st century America, the battle for gender equality persists. In nearly a century after it was first proposed in Congress, the Equal Rights Amendment’s (ERA) simple guarantee that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” is still seen as a radical notion by some.

Yet despite opposition and obstacles, the ERA is closer than ever to enactment. Our 18th century Constitution — drafted without the inclusion of women, people of color, native people, or immigrants — is the most difficult to amend in the world. Yet, the ERA has met all of the Constitutional requirements for amendment set out in Article V. It has been passed by two-thirds of both houses of Congress and ratified by 38 state legislatures.

Now is the time to overcome the remaining hurdles and permanently enshrine the ERA in the Constitution where it belongs. In doing so, the US would join the ranks of every other democratic nation across the globe, all of which already protect women in their constitutions. The ERA has the potential to inaugurate a society-wide effort to repair systemic sex-based inequality and dismantle structural gender discrimination, far beyond what our existing laws protect. It will inspire a new generation of leaders to revisit and modernize the constitutional ideal of equality for all rather than settling for a broken system.

With the midterm elections upon us, the fight for equality and justice has taken on new urgency. As political polarization and ideological extremism intensify, core tenants of settled law such as reproductive rights and voting rights are unraveling. Without explicit constitutional protection for sex equality, the hard-won victories of social progress can be reversed by politicians and judges and by unexpected crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. Without the ERA, the rights of women and sexual minorities are not secure — and under this Supreme Court in particular, so much more is at risk.

Earlier this year, the newly-empowered radical majority on the Supreme Court eliminated the longstanding constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The logic behind the Dobbs decision makes it clear that other cherished rights are also in serious jeopardy, especially the right to marriage equality, contraception, and same-sex intimacy. Each of these rights is based on the understanding, rooted in the past sixty years of precedent, that the Constitution protects a set of “privacy” decisions — regarding bodily autonomy, family, intimacy, and marriage — from government intrusion. In Dobbs, the majority signaled its disdain for this doctrine.

In their dissent, Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan explained that “[a]ccording to the majority, no liberty interest” protects a woman’s right to make the choice not to proceed with a pregnancy “because (and only because) the law offered no protection to the woman’s choice in the 19th century.” The majority’s problematic logic, the dissenting Justices observed, would not only invalidate decisions that recognize and protect fundamental privacy rights such as those mentioned above, but could also impact the right to interracial marriage and the right to be protected against forced sterilization.

The ERA would provide a new textual basis for protecting reproductive rights and the related fundamental rights at risk. It would further anchor these rights as a basic matter of equality and equal participation in society, beginning with the ability to decide whether, when, and how to have a family. In fact, prior to the Supreme Court’s holding in Roe v. Wade (1973) that abortion was protected by the Constitutional right to make decisions about the most intimate issues facing women, many women’s rights advocates, most notably Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, believed that reproductive rights should be protected not only because of privacy concerns but also because it helped guarantee women’s equal treatment in society. Following the reasoning of the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in Bostock v. Clayton County — which held that federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in employment also includes sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination — the ERA could immunize other privacy rights such as marriage equality and same-sex liberties from the threat of Supreme Court reversal.

The devastating impact of the Supreme Court’s decisions from last term did not stop with Dobbs. The Court also struck down New York state’s 100-year-old restrictions on carrying guns in public, curtailed the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate the greenhouse gases that are causing global warming, and elevated religious liberty as a top-tier right, used as a justification to undermine other equally important individual rights. These decisions diverge far from public opinion and impose a shockingly narrow reading of our Constitution.

Given the Supreme Court’s new methodology of constitutional interpretation, the federal courts can no longer be relied upon to vindicate our civil rights.

And yet, there is reason to hope that with instability comes new possibility. Looking ahead, the ERA represents an opportunity to rebuild a stronger constitutional foundation for our country and its people.

This new framework would prioritize a substantive, rather than formal, approach to equality. The concept of formal equality — a sex-blind or sex-neutral approach to decision-making employed by the courts — can often end up blocking efforts to improve conditions for those who need help the most. On the other hand, substantive equality, embraced by transitional democracies such as post-Apartheid South Africa, acknowledges the roots of inequality with the goal of proactively lifting up historically marginalized groups.

In recent years, constitutional sex equality protections often have come to the rescue of men who claim they’ve experienced sex-based bias. Consider the recent decision from the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, Vitolo v. Guzman, which struck down a key provision of the COVID-19 stimulus package that fast-tracked the aid application process for restaurant owners who were female, people of color, or both. Notwithstanding overwhelming evidence showing that women- and people-of-color-owned businesses were hardest hit by the effects of COVID, Judge Amul Thapar (a Trump appointee) held that the government “failed to show that prioritizing women-owned restaurants serves an important government interest.”

The Vitolo decision illuminates why we need an ERA — to deliver on the promise of equality when existing constitutional prohibitions against discrimination have been ineffective in addressing widespread sex- and race-based inequality. Without an ERA, the clearly documented disadvantages suffered by women and people of color, presented and ultimately rejected in Vitolo, would not be adequately addressed despite the aims of strong government public policy to do so.

Instead, courts and lawmakers could apply a substantive equality framework. In the area of family leave, for example, lawmakers could consider the distinct needs that women have compared with men and therefore ensure that women have adequate paid family leave, along with additional support systems such as housing, food security and childcare services.

There is reason to hope. The ERA is closer to final ratification than ever before. While the ERA has met all of the constitutional requirements for ratification, the main legal obstacle that remains involves a time limit for ratification that was in the preamble to Congress’s initial authorization of the ERA in 1972. This time limit expired in 1982, well before the final three state ratifications in Nevada in 2017, Illinois in 2018, and Virginia in 2020.

History shows that the process for constitutional amendments has never been clear cut, as scholars David Pozen and Tom Schmidt have explained. The legitimacy of the congressionally imposed time limit, which has no basis in the Constitution itself, is contested and should not stand in the way of the ERA now that it has been ratified by 38 states. Critical towards putting the ERA in the Constitution, Congress is currently acting to remove the deadline, with the House of Representatives passing a joint resolution in two legislative sessions in 2020 and 2021, and the Senate currently considering the matter.

A vibrant, multi-faceted movement for constitutional gender equality is growing. The ERA has sparked new engagement at the state level, where 26 constitutions already contain state-level ERAs. In this midterm election, Nevada voters will be deciding whether to add an ERA to their state Constitution that would broadly protect equal rights regardless of sex, as well as “race, color, creed, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, disability, ancestry, or national origin.” Legislators in New York state also achieved first passage of their state ERA, even more expansively worded than Nevada’s to additionally protect abortion and pregnancy outcomes. This past year, lawmakers in Maine, Minnesota, and Vermont have taken substantial steps toward amending their constitutions with ERAs that would protect and promote equality more robustly.

The ERA has the potential to deliver on the unfulfilled promise of our nation’s founders to protect “justice for all.” We should take hope from the long and slow progress of a multigenerational and intersectional movement of concerned citizens to amend our constitution with an ERA. Working together, we can create a “more perfect” union. This election cycle presents a chance to rebuild our Constitution and country on stronger foundations. Those of us who care about gender equality should support candidates who make the ERA a priority and contact elected officials about the importance of securing final ratification of the ERA. Expanding popular support for the ERA is also critical and can be accomplished through increasing civic engagement in our communities and sectors, engaging youth on the importance of the ERA, holding public conversations in educational institutions, libraries, town halls, and advocating for State ERAs and state ratifications of the federal ERA.

A constitutional ERA would strengthen our participatory and pluralistic democracy. It would benefit all, no matter the ideology — protecting those who wish to be free of government intrusion into the most intimate decisions in one’s life and providing a mechanism for transformational social change to improve the lives of the most marginalized and ensure equality. The conversation is far from over — in some ways it is beginning anew.

About the Author:

Ting Ting Cheng is the Director of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) Project at Columbia Law School’s Center for Gender and Sexuality Law.

Ting Ting was the Legal Director of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington and served on the National Organizing Committee. She was a Foreign Law Clerk at the Constitutional Court of South Africa for Justices Albie Sachs and Edwin Cameron. In addition, Ting Ting was a Fulbright Scholar to South Africa where she received the Amy Biehl Award.

***********

Acknowledgements:

A special thanks to Marcy Syms for her support and collaboration on this piece.