Facing the Mountain, Facing the Truth: An Historical Look at Internment of Japanese Americans and Reparations

A Discussion with Daniel James Brown

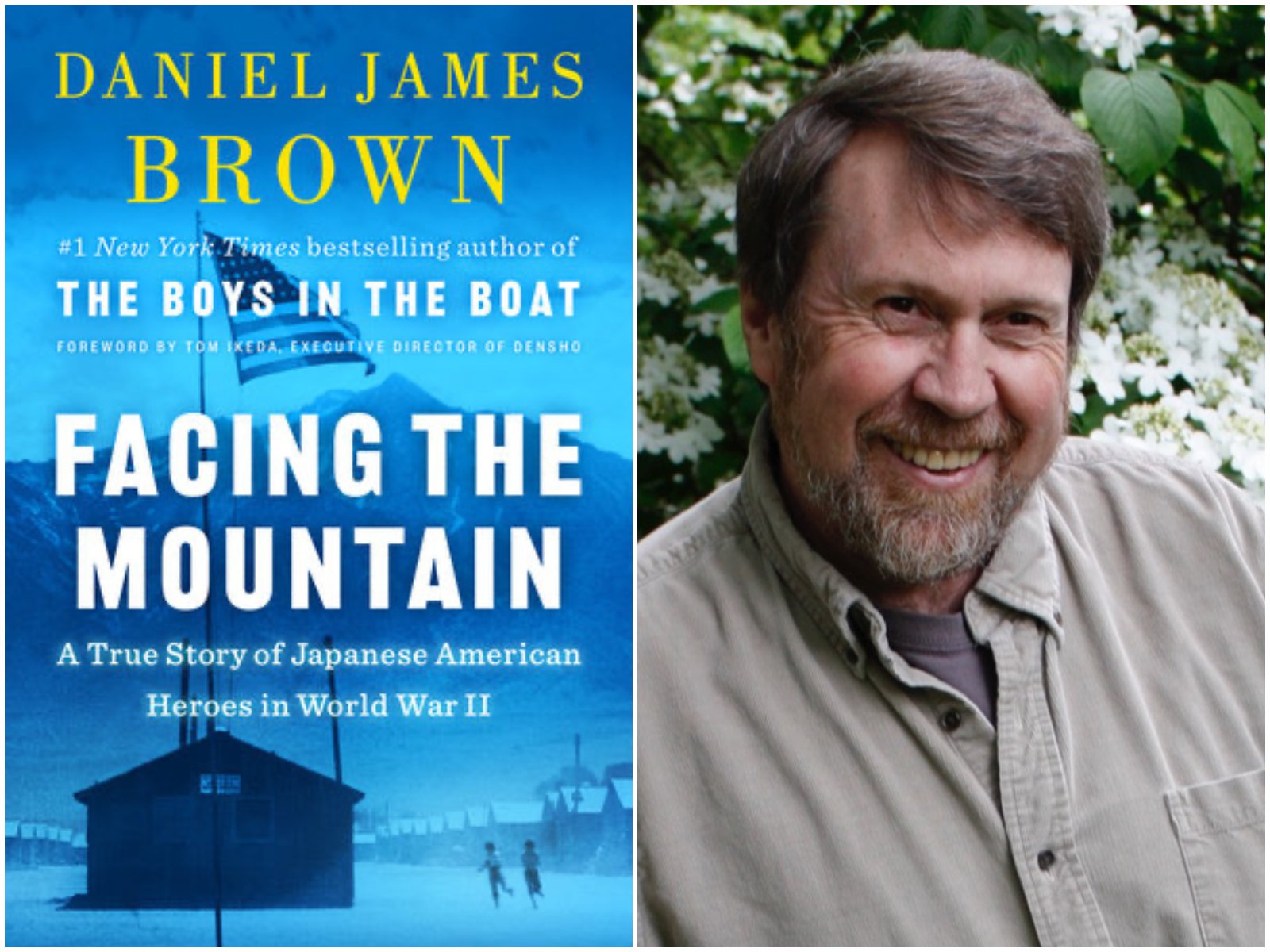

Daniel James Brown is the author of many books, including New York Times Best Seller The Boys in the Boat. He attended Diablo Valley College in the San Francisco Bay area, the University of California at Berkeley, and UCLA. He taught writing at San Jose State University and Stanford University. He states in his website that his primary interest is in bringing compelling historical events to life.

The author who inspired readers with The Boys in the Boat, Daniel James Brown, leads us on another historical adventure, this time following the lives of four young Japanese American men, three who fought in WWII for the United States, and one impressive conscientious objector. Many of these men, as well as over 100,000 members of their families and communities, were forcibly removed from their homes in 1942 and locked behind barbed wire for years in internment camps. In Brown’s latest book, Facing the Mountain, he tells their stories.

Concentration camps -- here -- in the United States? Although barely taught in U.S. schools, stories of the incarceration of innocent Japanese American citizens and families have drawn renewed attention. Long before the United States entered the war in December, 1941, anti-Asian animus had been growing in this country. After the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor, the animus turned into widespread fear and suspicion of espionage.

Japanese Americans who had lived quiet, dignified lives within established communities found themselves openly reviled by their neighbors and by newspapers and politicians. Japanese Americans were widely portrayed as vermin in editorial pages and posters.

Just two months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the War Relocation Authority to lock up over 100,000 Japanese Americans, more than two thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, Every Japanese American along the West Coast including doctors, lawyers, students, business owners and farmers alike were rounded up. They had not committed any crimes, yet men, women and children were ordered to leave their homes, turn over their businesses and farms, abandon their farm animals and family pets, and take only what they could carry. They were given as little as six days to leave.

The language used by the government and echoed by major newspapers to describe what was happening was, as Brown says, Orwellian. The families were “evacuated,” put on buses and trains, often at gun point, and jammed into “assembly centers.” They were ultimately transferred to desolate “relocation centers,” which were in reality heavily guarded concentration camps in desert areas of Idaho, California, and Arizona. Most of the “evacuees” remained confined until late 1945 at the war’s end.

Those who chose to go to war, went. In the second part of the book, Brown focuses on four young Japanese American men, second-generation citizens (Nisei) who had been born in the U.S. All were determined to prove their loyalty to the U.S., and, even though their families were locked up, three of those four volunteered to fight and joined the all-Japanese American army unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

The 442nd became known as a highly effective unit, feared by German troops and sought after by U.S. Generals. The men in the 442nd fought in hellish conditions in Italy and France, ultimately arriving in Germany where they were part of the divisions that liberated prisoners at slave labor industrial sites surrounding Dachau. At the end of the war, they were recognized as the most highly decorated U.S. military unit of its size and length of service, ever.

The fourth man showcased by Brown was Gordon Hirabayashi, who became an outspoken conscientious objector. He argued his case up to the U.S. Supreme Court, and lost. Years later he was honored, posthumously receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama.

Anti-Asian Sentiment continued. After the war, as Japanese American veterans returned to the mainland of the U.S., for the most part, they were not received as conquering heroes. Instead, many were denounced and told they were not welcome in their old neighborhoods. Similarly, families released from detention were ill-treated when returning home. Brown documents a number of such stories including one from Salinas, California. When the first few families started to return to the area, threatening notices appeared in the Monterey Peninsula Herald. The notices were anonymous, but they solicited funds and invited others to join the “Organization to Discourage Return of Japanese to the Pacific Coast.”

Most of the families returning to their former homes on the West Coast had lost everything. Unless their belongings, homes, businesses and farms had been left under the care of trusted white neighbors, they found chaos upon their return. Personal property had been looted and farms and equipment seized or sold for pennies on the dollar. Many of these Japanese Americans -- incarcerated by the U.S. government for years without due process -- had lost not just their brave and loyal sons overseas, but also their liberty, their property, and their very dignity.

New Leaders in Hawaii. The Japanese American veterans returning to Hawaii fared better. Their parents and grandparents had immigrated from Japan to Hawaii decades before to improve their lives by working on the sugar and pineapple plantations. They comprised a large percentage of the Hawaiian Islands’ population and they assimilated more easily. Many used the GI Bill to continue their education. Some went on to law school, becoming political and business leaders in Hawaii. One returning veteran of the 442nd was Daniel Inouye, a distinguished U.S. Senator from 1962 to 2012. Because of the efforts of Senator Inouye and others, laws were changed in Hawaii conferring new rights and powers for native Hawaiians and Asian citizens.

Redress and Reparations. Although many Japanese American families preferred to put this sorry part of their history behind them, many others demanded redress. In the late 1940’s, they began to seek formal apologies and reparations from the U.S. government. President Truman warmed to the concept, but it took 40 more years for the idea of reparations to take hold.

Finally, after years of demands for a government apology by the Japanese American community, and with the support of Japanese American elected officials like Senator Inouye, a federal commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was created. In 1983, the commission recommended that Congress and the President issue a formal apology. Quoting the author, “On August 10, 1988, after initially opposing the legislation, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the language of which declares that the incarcerations of Japanese Americans were ‘carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage, and were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.’ ”

Each survivor of the internment camps received $20,000. Although this was a pittance compared to their losses, when combined with the government’s apology, supporters of the movement deemed this to be a significant step forward. This provides a model and history lesson well worth considering as the United States makes decisions about other proposed reparations.

Sally Bagshaw: You have spent over a decade researching facts and personal stories from the 1930’s and 1940’s for The Boys in the Boat and Facing the Mountain. Why do you feel these stories are important to understand now?

Daniel James Brown: I've spent a lot of time researching the rise of fascism around the world in the 1930’s, and it is truly terrifying to me to see the parallels that we see unfolding now. A large segment of the conservative media has aligned itself with former President Trump and his allies. People proudly use the words “alternative facts.” I don't like that, because “alternative facts” are, in fact, lies.

Take “The Steal” and January 6th as examples. Court after court rejected allegations of voter fraud. And some in Congress still try to argue that the attack on our Capitol wasn’t as bad as it looked. There’s a boldness about lying in the public space, even amongst people who proclaim themselves to be journalists, that I don't think we've seen since the 1930s in Europe.

Bagshaw: Is there an antidote to “alternative facts”?

Brown: In the 40’s, it took a world war. Now, I think the only antidote is to be brutally honest in our assessment of our own reality and be utterly insistent on facts. Part of the insistence on facts comes in telling our history honestly, and that leads us back to the importance of Facing the Mountain.

Bagshaw: You said in your book “Politicians who had long known how racial hatred could fuel campaigns and advance legislative or personal agendas seized a ripe opportunity, and their rhetoric quickly became brazenly toxic.” You quote Representative John Rankin of Mississippi from the December 15, 1941 Congressional Record, “This is a race war...I say it is of vital importance that we get rid of every Japanese...Damn them! Let’s get rid of them now!”

Are politicians playing this racial animus card as effectively now as it was used in the 1930’s and 1940’s?

Brown: Hatred and lies continue to divide us. Sometimes hatred is expressed in coded language against Asian Americans, Black Americans, indigenous people, or immigrants; sometimes it is spoken shockingly out loud. Just look at Fox News, where the network propagandized the lie that Democrats had stolen the election from President Trump, or listen to Rep. Jim Jordan, who refused to certify the election, and by sheer repetition manufactured his own “evidence.” The brazenness of telling a lie, then telling it over and over, makes it potent and real with a subset of Americans. It is a huge problem. But for genuine intensity, listen to the recent testimony of the Capitol Police before Congress who were in the middle of the January 6 riot. They will tell you what real crowd hatred feels like.

Bagshaw: Can truth prevail?

Brown: Yes, but it will take courage from all of us. We must make our history, our telling of history, more inclusive and more honest as we come to terms with what we have done in this country. In regards to indigenous people, in regards to Black Americans, in regards to a whole number of racial minorities in particular. In books like Facing the Mountain, we need to start telling the full truth about what happened to Asian Americans. We have to start being honest about our own complete history if we want to avoid wandering down that same path.

Bagshaw: One of your underlying messages in Facing the Mountain is that rights of honorable citizens, over 100,000 of our neighbors in 1942, were absolutely trampled with only a few religious organizations -- notably the Quakers -- standing up for the Japanese American neighbors. Can we avoid something this terrible happening again?

Brown: One of my main heroes, a principled young Japanese American citizen named Gordon Hirabayashi stood up to the FBI and even more courageously stood up to his mother. He stated “There is nothing wrong with the Constitution...If the promised protections did not materialize, it is because those entrusted to uphold it have failed to uphold it. Ultimately, the buck stops here, with me, with us, the citizens...It is up to us.” We must take his warning seriously, stand up to the bullies, call a lie a lie, and protect those who need our help.

Bagshaw: Can reparations or some form of redress help us look honestly at our history and build healthy new relationships?

Brown: It took a long time to gather the power and the influence and to do the lobbying that was necessary to get Congress and ultimately a series of Presidents, culminating with President Reagan, to actually look at this and say yes, we have to do something about what happened to Japanese Americans; this happened and it's a stain on this country. The $20,000 wasn't the point. It was the apology and the reality of an actual payment that made a huge difference in morale and in self-respect.

Bagshaw: Can we use the model of Japanese American reparations to evaluate the historical facts and compensate our African American and Native American citizens too?

Brown: Yes, the model can be a starting point. We say that facts matter. They do. We're talking about millions of people in the case of African Americans descended from enslaved people. Enslaving human beings is literally the darkest part in our history. We will debate for a long time whether the progeny of those enslaved are due reparations. But there’s no question that treating people so reprehensibly under Jim Crow needs to be honestly evaluated and calculated, and some form of redress made.

Bagshaw: Many have said that what happened to Japanese Americans cannot be equated with the suffering of Black Americans. What is your response?

Brown: Across our nation, we must draw a bright line and tell the truth about the pain inflicted on individuals and families who experienced the terror of enslavement and lynching, who could not accumulate wealth by buying homes because of gross racism and egregious practices like redlining. And for Native Americans, we must expose the truth that their land was stolen from them, their children forced into English-speaking schools, separating them from their families and their culture. If we are going to be united as a country, it is very, very important to insist on the factuality of these actions. I think paying reparations to those who have suffered injustice, or to their descendants, is one way to honestly address our history and acknowledge the pain inflicted by the government and by those who did not stand up for justice.

Bagshaw: Redressing past injuries is going to be important yet challenging. We can expect significant opposition from some, and resentment from others, that any calculation, no matter the amount, is insufficient. What are your thoughts on how we proceed?

Brown: I recognize that any check cut will be symbolic and whatever the amount is, it's not likely to be big enough to really change people's lives profoundly. That said, taking the time for the conversations, raising up the facts, arguing about the calculations, and committing to new cross-cultural connections will be valuable. In my experience, when people actually get to know somebody of a different culture or religion or racial background, the barriers fall away pretty quickly.

Ultimately, any redress or reparations check -- along with an official apology -- will represent truths that have not to date been recognized. Those are important steps forward.

******

Sally Bagshaw would like to thank Daniel James Brown for this interview, as well as Tom Ikeda, Executive Director of the Densho Project, who provided much of the historical information and interviews upon which Facing the Mountain was based.

About the Author:

Sally Bagshaw is a Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative Senior Fellow, former three-term Seattle City Councilmember, and Chief Civil Deputy for the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office. Sally is a lawyer, mediator, and advocates for government that functions responsibly.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.