Unveiling the Power of Art to Create Social Change

Q&A with Kat Owens, Ph.D.

Katharine Owens is a National Geographic Explorer and Fulbright Nehru scholar. She is also professor and chair of the Department of Politics, Economics, and International Studies at the University of Hartford in Connecticut. Trained in both art and science, Kat has been working for decades to address plastic pollution as an existential threat to animals and to the environment. Her work seeks to continually push the boundaries between art and science, using the arts to explore pressing political and environmental problems.

I met Kat on a Lindblad-National Geographic expedition to the Arctic, where she was engaging participants in art focused on social impact. Subsequently, I had the opportunity to pose a series of questions to her on the role of art in addressing important social issues and its effectiveness in building awareness of critical challenges and commitment to social change.

Sandra Kresch: Your academic work focuses on civic engagement, politics, and environmental problems. What made you build a connection between these social policy challenges and the arts?

Kat Owens: My first bachelor’s degree was in Studio Art, primarily focusing on printmaking and painting. I took a break after completing that degree, then returned to study Biology and Anthropology, getting undergraduate degrees in both. Then I moved on to complete a Masters in Environmental Studies and a Ph.D. in Governance and Sustainability. Even though I moved more into the sciences and social sciences professionally, the arts have always been an important part of my life. I am a visual learner — drawing and sketching helps me understand problems more deeply. As a tenured professor, I became increasingly comfortable with re-integrating the arts into my teaching and research.

I see connections between the arts, the sciences, and the social sciences everywhere. Early explorers and naturalists, who we think of as ‘scientists,’ were often also accomplished artists. What would political movements in the 20th and 21st centuries be without posters promoting politicians, issues, or resistance movements?

In my work I am trying to use the arts not just to illustrate a point, but also potentially as a tool for gathering evidence and data. I’ve been reading the work of researchers who highlight how artists and scientists “draw on a common toolbox of cognitive approaches” to build knowledge (Chappell and Muglia 2023, p.1). They promote “expanding practices considered to be science and reframing art as a central dimension of scientific work,” which they believe “may yield insightful discoveries” (Chappell and Muglia 2023, p.1). Jung et al. (2022) write that the value of collaborative Art/Science is its power to “envision [ ] previously unimagined possibilities, and establish [ ] and strengthen [ ] relationships with diverse stakeholders through long-term mission-driven or place-based inquiry” (Jung et. al, p.1). Sharp observation is required for both art and science, and I believe that artistic exploration can complement scientific discovery. I’m determining what this might mean in my practice., and the sketchbook we talk about later demonstrates how I am trying to push that boundary in my work.

I believe the visual documentation of the landscape that is the output of our shared Lindblad-National Geographic expedition to the Arctic stands as a record of a moment in time. While it is ‘pretty’ and ‘inviting’ as an artistic record, I also believe it is a scientifically valuable record of a landscape, which when compared to images of that region from the past and future can help catalog change over time. But this is a new approach for me — to work explicitly to use art to gather scientific data — and I would describe it as a burgeoning practice. There are interesting things happening around the world in this space — in addition to the researchers quoted above, Ocean Networks Canada has created an artist-in-residence program, Dr. Matthias Rillig at the Freie Universität in Berlin invites artists to collaborate, and the European Marine Board is also hosting an artist-in-residence program. These programs often seek a collaboration between an artist and a scientist or scientific team. What makes my work a little unique is that I am both an artist and a scientist.

Kresch: You challenge your students to tackle complex economic, public, and environmental policy problems in ways that result in real world social impact. What are some examples of how the arts support these social impact initiatives?

Owens: In my classes, I hope to expose students to new ways of thinking about policy and politics. During the last presidential election year, I taught a course called The Political Image. It was an ideal moment to explore political images being produced on social media, for example, in real time. In this class, we viewed political art, including Martha Rosler’s The Living Room War, in which she juxtaposes magazine spreads of pristine home interiors with images of war and chaos. I interpret the work as asking the audience to recognize how our lives, which for many of us are safe and protected, exist at the same time as horrendous global political events. The world has not changed much since Martha Rosler’s time. We can still insulate ourselves from the problems experienced around the world. Just as Martha asks the viewer to acknowledge the co-existence of beautiful American homes and the destruction of war, I want to challenge my students to think about the ways their lives connect to and are separated from global political events. My students created their own collages of interiors and destruction in the style of Martha Rosler.

We also learn about the Taring Padi movement, a decades-old collective of political artist-activists from Indonesia that creates everything from street theater to puppet shows, to woodblock prints and posters. Together, the students and I hand-carved and printed a wood block poster about civic engagement and voting.

I share the book Dear Data by Giorgia Lupi and Stefani Posavec, a project wherein two friends sent postcards to each other weekly, challenging themselves to visualize data about something happening in their lives that week. For example, for one week they collect data about how many times they check a clock, choosing to illustrate these data in different ways. My students create postcards for data collection challenges and examine the way professional researchers visualize data.

I believe these assignments push my students to actively engage in learning and to think more deeply. Bringing scary social problems into our living rooms, even as an artistic exercise, forces us to acknowledge and reckon with them in a different way.

Learning how to express a political idea and share it widely as a wood block carving is a tactile skill, but it also requires reflecting about the social problem the poster addresses. I hope that through this assignment they have a deeper understanding of what is important to them, and also begin to see themselves as politically engaged citizens.

Understanding the symbolic shorthand used in political cartoons and memes can also help them connect with the political discourse, which they are sometimes actively avoiding out of confusion or disenchantment. Our current political landscape is daunting. Our access to social media and round the clock entertainment make it easier to check out completely from politics. I want my students to check in, and also to have a toolbox of skills that help them recognize how symbols convey ideas, so that they can see the subtext in the messaging around them.

Making sense of data and statistics is a kind of ‘literacy’ that is essential for everyone living in our society. We are inundated with numbers that can quickly make our eyes glaze over. Asking students to grapple with data about their daily lives, to determine how to record it, to categorize it, and to illustrate it helps them hone this statistical literacy and ideally will make them better interpreters of the numbers thrown at them on a regular basis.

In all these ways, I use the arts to encourage my students to reflect on and engage with social and political issues.

Kresch: Plastic pollution has been a significant focus of your work over the years. What is the problem you are trying to solve?

Owens: While I’ve studied water policy for just over twenty years, in the last decade or so I have focused on plastic pollution. Global markets produce upwards of 350 million tons of plastic each year; when you read the publicly available information produced by the plastics industry, they make it clear they would like this number to increase annually. Plastics take dozens to hundreds of years to break down, depending on the type of plastic and their disposal. To my mind, it’s stunning that we are producing millions of items a year designed to be used for a moment but will last as wastefor a lifetime or several lifetimes.

Most of the work addressing plastic pollution deals with what we call the ‘end of the pipe,’ for example, in clean-up initiatives or recycling programs. I recycle, but I also know that 90.5% of all plastic ever made has never been recycled. This is because it is not designed to be recycled. It is much cheaper for companies to use fossil fuels to make new plastic than it would be to reuse or recycle plastics they have already produced. What we envision as recycling — where an old water bottle becomes a new water bottle — is almost never the goal. At best, most single use plastics could be downcycled, or made into something else of lower quality than the original use. This is due to the properties of the material — which when recycled takes on a different, degraded form. I’m at a small teaching-focused university, so, my work emphasizes training communities to use simple methods to collect scientific data while they clean up beaches and riversides. I’ve had the opportunity to do this work in Connecticut and India, and in collaboration with other National Geographic Explorers in Indonesia and Uganda. My ultimate goal is to influence policy to reduce plastic at its source.

Kresch: How has art become a tool in addressing plastic pollution?

Owens: For many years, my work on plastic emphasized community outreach and education projects that sought to link scientific data collection with political advocacy. During the pandemic, my research was shut down. It was then I started thinking about using the arts to tell a different story about plastic pollution.

When you read the scientific literature, it is very common to see articles or reports that talk about the “dirtiest rivers in the world” or the “worst polluting countries.” They are often referring to countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia. In my limited experience in South Asia, I learned that grocery stores had the same kind of packaging that is common in the US. To my mind, it is not that we’re better at controlling the problem in the US, it is that we are better at hiding the problem. We throw most of our plastic waste ‘away,’ which is code for putting it in a landfill or an incinerator. Each of these ‘solutions’ has significant environmental consequences. I wanted to tell a story about the way people like me use and interact with plastic.

I started the Entangled and Ingested project in 2021, in which I am creating life sized portraits of some the animals harmed by plastic pollution. I create the portraits by hand sewing film plastic onto canvas.

White Faced Storm Petrel, 2021 by Katharine Owens, 22.25 x 18 inches (Photo by Soona)

Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle, 2021 by Katharine Owens, 38 x 33.5 inches (Photo by Soona)

Many of these film plastics — think mailers that your online orders are delivered in, bread bags, cat food bags, etc. — are stamped with the chasing arrows symbol and words that may say something like “please recycle.” When a consumer sees this recycling symbol on film plastic, they believe this means the material can be recycled, but manufacturers can stamp that symbol on film plastics knowing that they cannot be recycled. I believe this symbol misleads the public about the recyclability of film plastics. Film plastics are not recyclable curbside through public waste management in any community in the US. As a consumer, you may see this symbol and think: this is recyclable, but research and investigative reporting indicate that these plastics are not being recycled in practice.

I began Entangled and Ingested because I was trying to figure out what to do with the plastic film my family used. The first series, which I have completed, includes 46 life-sized portraits, most of which I made myself. The largest are created with the public, including a 60-foot by 20-foot sperm whale currently being exhibited at Bradley International Airport in Connecticut.

The 60-foot-wide life-sized Sperm Whale, co-created with the public in 2021-2022, hanging at Bradley International Airport in Connecticut, 2024 (Photo by K. Owens)

The artist with the 52-foot wide, life-sized portrait of the Bowhead whale, made with the public in 2022-2023 (Photo by Dan Nocera, used with permission)

I am now working on the second series of 73 species. I’ve done about ten of these so far. I just completed a 24-foot-long Orca portrait with elementary school kids from Middletown, Connecticut, and I’m working on the 51-foot-long Humpback whale portrait.

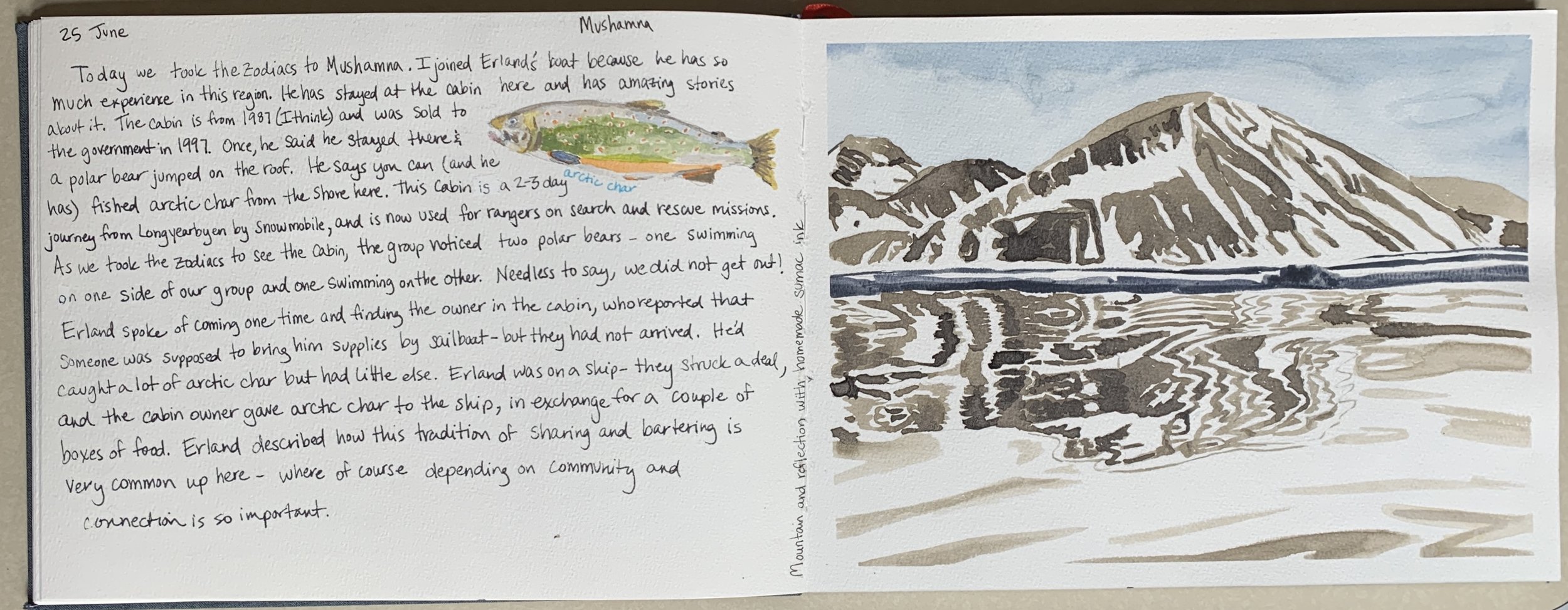

As a National Geographic Explorer, I had the opportunity to apply to accompany an expedition on Lindblad-National Geographic to the Arctic in 2023. My task on the voyage was to create a sketchbook of watercolors that recorded what we were seeing, especially through the lens of climate change and plastic pollution. We circumnavigated Svalbard, seeing stunning animals and landscapes along the way. Svalbard is a place where there are more polar bears than people, and yet when we stopped at remote beaches to hike, we found plastic pollution washed up on the shore. Being able to circumnavigate Svalbard at that time of year was possible because ice was receding due to climate change. In this way it was a bittersweet experience, seeing an incredible place while also worrying it may be slipping away.

Katharine Owens, Sketchbook, Longyearbyen, June 2023

Katharine Owens, Sketchbook, Mushamna, June 2023

Katharine Owens, Sketchbook, Cub with plastic, June 2023

I seek to push the boundaries of art as a tool for scientific data collection. In creating the sketchbook, I sought to record stories from the scientists, guides, and crew on board, who had years of experience in the region and could talk about how things had been in the past.

As a visual record, it may be most interesting as a comparison to watercolors created by other artists and explorers in the region from the past. I have been exploring this through an excellent site called watercolourworld.org, which allows one to pinpoint a geographic area and see watercolors made there over the last several hundred years.

In many ways, the story of the Arctic is one of change. I would love the opportunity to return to the region on an annual basis to continue to collect stories and record these changes over time. To be sure, scientists are making records of glacier height and depth, collecting ice core data and mean temperatures, and thousands of other data points about the region — but seeing a watercolor of those changes or reading firsthand narratives, is a different and complementary kind of evidence. Just as is the case with the colorful sewn pieces, I believe the watercolors connects us to the poignancy of the losses in the Arctic in a way that ice core data may not. Including them alongside traditional scientific data may be another way to reach audiences and communicate science about the changing Arctic.

Kresch: As an artist, how did you approach telling the story of plastic pollution and engaging people in understanding the importance of this issue?

Owens: My approach to telling the story of plastic pollution is similar to that of many researchers: I share facts from the literature to set the stage and build upon that work with my own research results. What has changed in the last decade is the way I augment this with the arts. I feel many people now know a good bit about plastic and its environmental harm. What I hope Entangled and Ingested can do is engage the people’s senses to make a stronger or perhaps longer-lasting impression.

Visual imagery is engaging and alluring. We remember images differently than we do facts or figures. I intentionally make the portraits life-sized, because I believe the scale of the works reinforces the scale of the problem. I intentionally make them colorful and engaging, because I believe it is appealing to the viewer — just as the packaging was designed to grab the consumer’s attention. I include the logos on the packaging because I know they are recognizable to audiences, even to the youngest viewer, and I want viewers to associate this issue with these brands. I made a conscious effort to portray animals, because they are the helpless victims of our excess. Through all of these strategies, I hope to build a lasting impression that stays with the viewer and connects differently than a research article would.

I share the Entangled and Ingested project in multiple ways. I have public exhibitions of my work — I’ve yet to show all 46 pieces of series one at once, but I am always on the lookout for a space that can exhibit two large whales (55 and 60 feet long) along with 44 other smaller pieces. I give presentations about the problem of plastic pollution, my research, and the arts projects to all sorts of audiences, from pre-school groups to scientific conferences. I also lead collaborative sewing workshops with schools, universities, community groups, and so forth. I believe that the tactile act of sewing film plastic gives people a deeper understanding of the issue and helps them recognize the plastics around us.

Kresch: When you began this initiative, what did you want the impact of your work to be? Beyond the art produced via this initiative, how have you evaluated its impact?

Owens: I have written peer-reviewed scientific articles for years. While they are of course very important for my professional advancement, publishing more scientific research is really ‘preaching to the choir.’ I want this project to inspire people to advocate for better policies on plastic.

In the first year of the project (2021), Entangled and Ingested reached about 1,700 people. In 2022, I shared it with approximately 3,400 people. In 2023, thanks to hanging several large pieces at the Durham Fair in Connecticut, about 28,000 people viewed the work. I am hoping to share it with even more people in 2024.

I am currently working to capture the impact of the Entangled and Ingested project through an online survey for participants over 18 that asks questions about behavior, choosing alternatives to plastic, the challenges of avoiding plastic, and whether they have contacted companies or politicians in the past about plastics. Then I ask several questions about their intention in the future to avoid plastics, to contact companies or politicians about plastics, and how they have interacted with my work (through a lecture, an exhibition, a workshop, or a combination of these things). Finally, I ask about how this issue makes them feel, how my project makes them feel, and what they think the solution to the plastics problem will be. While a rudimentary study, I hope it will shed light on the impact of projects like mine.

I’m still determining how to broaden the impact of the watercolor sketchbook. I now share it as a part of presentations about my work, have posted it to my website, and am looking for ways to share it with a wider audience. Most people will not get the chance to visit the Arctic, so I hope this will allow them to experience it from afar. I would love to create a traveling exhibit of images from the sketchbook combined with traditional scientific data, an exhibit to engage both sides of the brain, if you will, about plastic and climate change in the Arctic region.

Beyond this, I would love to collaborate with the museums that hold some of the earlier watercolors from this region to tell a story about how artists are recording this changing landscape. I have reached out both to the National Maritime Museum in London and the Scott Polar Research Institute to inquire about potential collaborations. I see all of this work not as a replacement for traditional scientific exploration and data collection, but as a way to approach new and different audiences or to broaden the impact of traditional scientific research. My sketchbook — the watercolor images and the journal entries — provide a rich history of the area that can help us catalog the ways it is changing.

Kresch: From an artistic perspective, how satisfying was this project? Were you to do it again, with the objective of producing excellent artistic work and significant social impact, what might you do differently?

Owens: The Entangled and Ingested project is ongoing — I plan to continue working on it through 2027 at least. It is highly satisfying as an artist to get the opportunity to explore a new material and to try to understand its potential and limitations. Sometimes I think of it in the same way I think of oil painting: a process of layering material to produce the desired result. But it also has the added challenge or benefit of not being able to mix a specific color or in having to use patterned plastic. I enjoy trying to figure out how to use the patterns stamped on packaging or the colors in front of me to achieve the results I’m seeking.

When thinking about the watercolor project — it was incredibly satisfying. I have this amazing book that encapsulates a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It is better than any photo album or slideshow. I had never traveled to the Arctic before and had no idea how much the landscape, the wildlife, and the experience would capture my heart. I would love to help bring the beauty of the Arctic to more people.

While I love the book I produced, I just visited an exhibit of book arts at the Maier Museum at Randolph College in Virginia called Back to Front: Artists’ Books by Women, and it made me realize how “inside the box” my thinking has been about my sketchbook. The exhibit featured artists’ books that really played with the idea of the page and included amazing things like unfolding pages and three-dimensional elements. If I get the chance to accompany another Lindblad-National Geographic Expeditions voyage, I will expand how I think about sketchbooks and how creative one can be with the presentation.

Kresch: Are there inherent conflicts between producing art and having impact on the social good or are these two goals compatible?

Owens: I do not think that these goals conflict. I believe art is what happens when we want to make something beautiful out of our pain. To me, using the arts to raise awareness about social or environmental problems is a natural fit.

Kresch: What have you learned from your work about the potential role of the arts as a tool to have impact on significant social issues? How can artists’ work engage the larger community in addressing the critical social issues of our time?

Owens: I reference several researchers in my presentation, who write about the potential of the arts to engage diverse learners, influence behaviors, aid communication, build knowledge, and develop empathy. All of this resonates for me when I am out sharing my art projects. I hope it can enable people to understand issues in a way that helps them advocate for societal change that is important to them.

I do not think there has been a great deal of research to date about the impact the arts can have in addressing social issues. Anecdotally and instinctively, though, something is there. I believe the arts can move us in ways that facts and figures cannot. I know some artists who adamantly reject the idea of measuring the impact of the arts, and I understand that perspective. I do not think it is necessary to see evidence on a chart or in a table to acknowledge the impact of the arts on people. I am not sure we can capture the way the arts can move us to think more deeply about an issue or consider our role in a societal problem. For my part, I do not expect dramatic immediate change from any of my work. I hope to plant a seed of thought. If the visuals are compelling, then I hope people will return to them and continue to think about the problem and how to fix it. To me, that is a meaningful impact.

About the Author:

Sandra Kresch has had a 40-year career focused on managing growth and change in consumer-driven businesses. She has worked extensively in the media and entertainment industries, building a range of nationally and internationally known businesses. A 2021 Harvard Advanced Leadership Fellow, Sandra has focused on the underlying causes of political polarization and the impact of identity and media in creating the environment in which polarization thrives. In addition to her business career, Sandra is a photographer whose work focuses on architecture and graphic details, primarily in cityscapes and rural settings. She has studied at the International Center of Photography in New York as well as with French portrait photographer Stephanie de Rouge and New York-based architectural photographer Jade Doskow. She is a Senior Editor in the Arts and Culture domain of the Social Impact Review writing on issues related to how the arts achieve social impact.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.