A New PK-12 Education Ecosystem Framework for a New Normal

Ecosystem: a biological community of interacting organisms and their physical environment

A Sense of Urgency: Inequities in Stark Relief

Like so many, I will never forget when our lives took a dramatic pivot in March 2020. I read an email from my Dean, Bridget Terry Long, notifying faculty, staff, and students that we would not be returning to face-to-face instruction after spring break. I would never have guessed at that time that my life, and the lives of so many, would be impacted in ways that none of us could have imagined. And while my life has been impacted, I am fully aware that I live a life of some privilege. I was privileged to shelter-in-place. I was privileged to continue my work via Zoom. Consequently, I was privileged to realize a steady income - despite the health pandemic and the subsequent economic downturn. During these trying times of health and financial strain, another social pandemic began to sweep the country, like a historical tsunami that had been pent up for far too long. Its release broke through George Floyd’s faint cry of “I can’t breathe.” As a black man with three black sons, I was not so privileged to avoid this racial and social pandemic. As a result of these trials, I began to hear the constant refrain, “When will things return to normal?” I could not help but think of this question in relationship to educating the most vulnerable students in America.

Contrary to those who are calling for a “return to normal,” I am under no illusions about a bygone educational golden age. What was normal was never acceptable, particularly for children from the most marginalized communities. The crisis of COVID-19, the resulting economic downturn, and the racial reckoning the country is now experiencing have made the need for equitable, high-quality education even more urgent. Fortunately, all three crises are at the top of new Biden-Harris administration’s ‘To Do’ List. Instead of returning to normal, I propose that we create new ways of doing work, especially for those whom a quality education is a way up and out of poverty. Part of the answer is in bringing together communities, policymakers, researchers, investors, and technical assistance providers to work alongside and in sync with schools and communities.

Re-envisioning One’s Impact

Doing this work differently has implications for individuals no matter where they are on their career continuum. In other words, the career path of an educator was once linear. He or she would graduate from a university, obtain a teaching position in a public school district, and, in many cases, stay in that position until retirement. A few would transition into school leadership or some other leadership role, while others would pass year after year in the same classroom - a noble calling indeed. Outside influences were rare: the city, state, and federal governments would allocate funds, but otherwise, key decisions affecting teachers and students were made in the schoolhouse.

Today’s educators, as well as those looking to impact the lives of the nation’s youth, face a dramatically expanded and more complex environment in which they can leverage their knowledge, skills, and passions to influence educational and social outcomes. And our current crisis-laden environment necessitates a new way of “thinking” about the work we do as well as how we “actualize” the work we do. I argue that the urgency of our times requires a shift in our thinking if we are going to have accelerated and deep impact in communities.

Students in the masters and doctoral programs for which I serve as a faculty member often ask me, “What should I do after I graduate? What job should I apply for?” For several years, I would attempt to answer those questions. I would connect them to colleagues whom I had met over my 30-year career or help them research job postings. I focused on positions and titles - instructional coach, program director, data analyst, principal, foundation executive, superintendent - and so did my students. Over time, I have come to realize that there is a more helpful way to advise those seeking to transform and improve the lives of students and communities. What these all have in common is a desire to have a deep and lasting impact. My advising now begins with asking a different question altogether. Instead of asking, “What job should I apply for?” I believe emerging education leaders should ask themselves, “What impact do I hope to have?” This reframing opens the door to new possibilities that have emerged - particularly over the last decade - because of shifts in education policy and funding, which have expanded the education ecosystem to be broader than ever before.

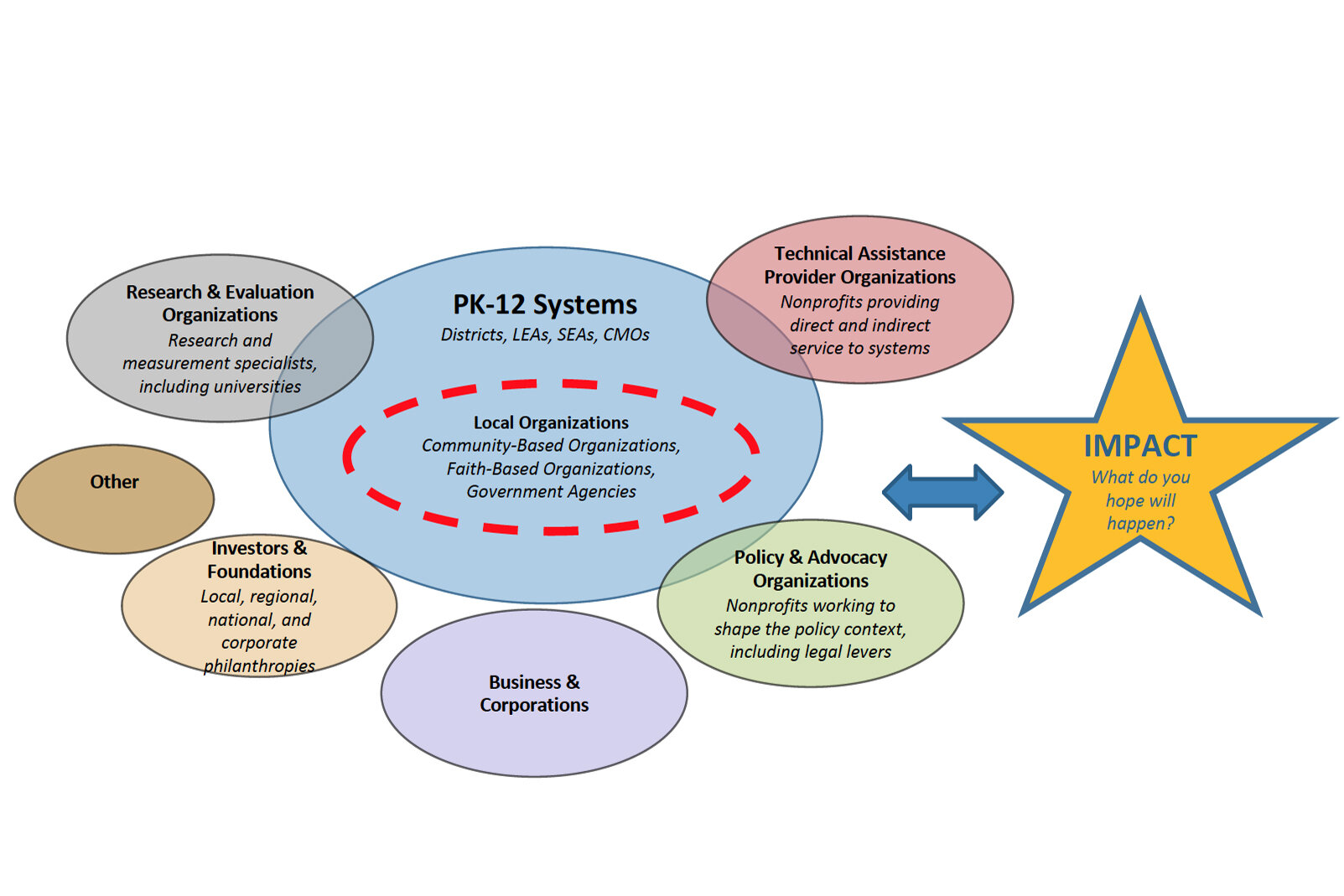

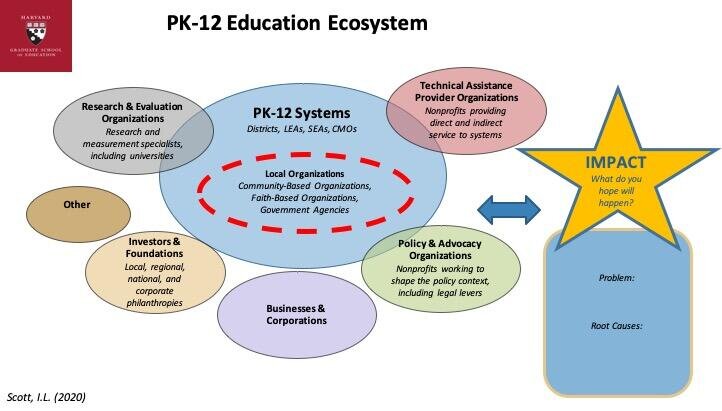

The PK-12 Education Ecosystem Framework [Figure A] is designed to offer a more holistic approach to supporting students and communities. The framework’s benefits are twofold: (1) it offers a way for individuals to think about the impact they aspire to have on America’s most vulnerable children and communities, as well as how these individuals might live out that aspiration in their careers, and (2) it provides tools for communities to understand how they can leverage human and financial capital through the various parts of the Education Ecosystem to ensure individual impact at the student, family, and community levels. The following is a brief overview of the framework.

THE EDUCATION ECOSYSTEM FRAMEWORK

Figure A below displays the PK-12 Education Ecosystem Framework.

PK-12 SYSTEMS

At the center of the framework are PK-12 systems. This is intentionally depicted as the largest oval because it contains the most resources, more than $700+ billion in public spending, mostly from state and federal coffers. Encompassed within this component are the more than 3.5 million teachers who lead America’s classrooms within school districts, local education agencies (LEAs), and charter management organizations (CMOs). It also includes state education agencies (SEAs) and regional education service agencies (ESAs), which enact policy and provide resources, including professional development and guidance, that affect students in schools.

Some of the most common professional roles in this circle are teachers, coaches, grade - level leaders, and principals, as well as superintendents, district cabinet members, and leaders of offices focused on curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Examples of organizations represented here include Boston Public Schools, New York City Department of Education, Aspire Public Schools, the Tennessee Achievement School District, the Bureau of Indian Education, and the Department of Education of Puerto Rico. This element of the ecosystem also includes independent schools and faith-based schools, which provide an opportunity to learn across traditional school boundaries.

LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS

Nested within the PK-12 system are local organizations. These include community-based organizations (CBOs), faith-based organizations (which include houses of worship as well as the nonprofits that are often associated with them), chapters of national service-based nonprofits, and government agencies that support children and families. The importance of these organizations is sometimes underappreciated, yet they often have deeper relationships with children and families than schools because they operate 365 days of the year, instead of just during the 180-day school year. As a result of COVID-19’s impact on communities, these organizations will be even more critical in supporting students’ and communities’ needs. These organizations are highly trusted and relied upon by community members for the many benefits they offer.

Examples of organizations represented here include those with a national footprint - National Urban League and Logan Square Neighborhood Association - and local organizations such as Boston’s Freedom House and Hyde Square Task Force. Government agencies such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Human Development, public library systems, and local public-housing authorities also provide social-service support to children and families that could be better aligned with PK-12 systems.

TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROVIDER ORGANIZATIONS

Simply put, these organizations work in partnership with those parts of the ecosystem that provide direct service to students and communities. For example, these organizations design curricula, provide professional development, and offer tools to help teachers and school professionals do their jobs more effectively. The number of these organizations grew significantly during the administration of President Barack Obama, under whom the U.S. Department of Education required states and districts to meet certain parameters to access new funding streams. These federal requirements led states to adjust their teacher evaluation systems and to raise standards for student learning in unprecedented ways. To make these shifts, districts and states increasingly called upon outside experts, many of whom worked with multiple states simultaneously to help scale new practices. These organizations typically benefit from individuals who have had experience in schools and districts. These individuals bring a first-hand perspective of teaching, learning and leadership in schools.

Some influential technical assistance providers include The New Teacher Project, LearnZillion, Achievement Network, Zearn, WestEd, Education Resource Strategies, and Achieve The Core. Supports that these organizations provided to districts and states include, but are not limited to, supporting the development of ‘Race to the Top’ proposals to the U.S. Department of Education; co-designing and implementing new teacher evaluation, support, and retention systems; aligning district-wide instructional models to new state standards; and developing new funding models to support new work. While many of these organizations grew in response to the demand at the time, many of them still exist today because of the value they add to schools, districts, and states.

POLICY & ADVOCACY ORGANIZATIONS

Policy and advocacy organizations do not provide direct services to students, but in many ways, they create the conditions under which the PK-12 system functions. These organizations push for high levels of curricular standards, meaningful teacher credentialing, and adequate resourcing for schools that serve the most vulnerable learners, to name a few. They aim to catalyze change by influencing legislation, policies, and funding. Many of these organizations do evaluation and research that informs policy positions and activism. They also provide training and support to organize constituents. They also consider the legal levers that can be pulled to impact strategies and outcomes.

Important organizations in the policy and advocacy space include the Council of Great City Schools, American Federation of Teachers, American Enterprise Institute, Education Trust, Center for American Progress, and the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Roles may be focused on policy analysis, communications and outreach, data management, government affairs, and advocacy strategy development.

RESEARCH & EVALUATION ORGANIZATIONS

Research and evaluation organizations design and run tests or experiments to determine what works in education. These organizations are only rarely well-integrated into PK-12 systems, which means that new curricula are often piloted, and new programs are often launched without a thoughtful approach to eventually understanding the efficacy of those efforts. PK-12 systems would be well-served by integrating more intentionally with organizations in this area to know whether they are achieving intended results and whether their efforts are leading to disparate impacts on different populations of students.

Examples of research and evaluation organizations include RAND Corporation, Mathematica, MDRC, Mission Measurement, and university-based research organizations like Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research.

INVESTORS & FOUNDATIONS

Investors and foundations play an influential and sometimes controversial role in the PK-12 Education Ecosystem. Most foundations form theories around solutions and then make investments based on those theories, rather than designing and running their own programs. Accordingly, in this framework they do not overlap with the PK-12 system directly, unlike most of the other circles. Foundations make strategic investments to enable work to happen, not only by giving directly to PK-12 systems and nonprofits, but also by contributing to policy and advocacy, aggregating knowledge, and supporting research. Many times, these investors will engage strategy development firms such as McKinsey and Company, The Bridgespan Group, EY Parthenon, and Bain and Company to co-construct plans to be tested and implemented. Another unique role foundations play is to provide incentives for members of the ecosystem to work collaboratively, rather than operating in isolation. There is a growing and encouraging movement to ensure that the work of investors and foundations is done with rather than to communities. This is the approach that Dr. Dorian Burton takes at the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust.

Investors most commonly take the form of local, regional, national, and corporate philanthropies, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Nellie Mae Education Foundation, Boston Foundation, and the Barr Foundation.

BUSINESSES & CORPORATIONS

Businesses and corporations are oftentimes overlooked in conversations regarding PK-12 education. They play two major roles in a thriving education ecosystem. First, corporations provide expertise and resources for schools and districts. Like philanthropic organizations, businesses and corporations are also in a great position to support locally based efforts in communities. We are already seeing examples of this happening in response to the George Floyd murder and long-standing structural racism in the U.S. Major corporations like Apple and Google are not only messaging a change in their business practices, but they are also pledging investments to address these long-standing inequities, including in the realm of education. A second way that businesses and corporations should be leveraged more in the education ecosystem is by helping to bridge the gap between schooling and career opportunities. This approach would look different in different communities; however, one goal is for students to see the link between their K-12 schooling and college and or careers. Another goal is that “every employer has a talent pipeline of young professionals with the skills needed to contribute to and lead the workforce.” Organizations like Jobs for the Future and New Profit’s Future of Work Grand Challenge are excellent innovative examples of how businesses and corporations can assist in transforming the lives of students and their communities.

A note on categorizing organizations:

It should be noted that some organizations exist in multiple categories. Take Summit Public Schools, a charter-school network in California and Washington that also runs a teacher residency program and an online learning platform used by nearly 400 schools across the country. Or consider a graduate school of education that conducts research, trains teachers, offers professional development programs for practitioners, and employs faculty members who provide technical assistance to school districts. While some organizations may not fit neatly within a single circle, the key is that no matter where they fit, optimal impact can be achieved when they are attuned to and aligned with others in the ecosystem.

Applying the Framework

One way to use the PK-12 Education Ecosystem Framework is to help practitioners position themselves for impact. A classroom teacher with a total class load of 100 students may not know how his work fits together with that of a colleague next door in creating a coherent educational experience for a ninth grader, let alone understand how his work fits as part of the broader PK-12 Education Ecosystem. The PK-12 Education Ecosystem Framework is designed to help practitioners “get off the dance floor and go on the balcony,” in the wise words of Harvard Kennedy School faculty members Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky.

After a long career on the “dance floor” as a teacher, principal, district administrator, and nonprofit leader, it was only in my role as Deputy Director of Education at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation that I was able to understand fully the roles of different players in the ecosystem. I led a $300 million investment portfolio to transform teacher evaluation practices, and one of the biggest successes of our work was the way we were able to align each of the circles in the ecosystem in service of the goals we and others saw as important. For example, we worked with a host of teachers, advocacy partners, technical assistance providers and researchers to find new and innovative ways to measure and enable great teaching in schools. We could never imagine doing this work for teachers, without teachers, so we engaged teachers from across the U.S. At times, the work was difficult, but it moved forward because of deep, aligned engagement from multiple parts of the ecosystem. Achieving that level of alignment is difficult, and it can feel unnatural to organizations that have grown accustomed to working somewhat autonomously. It is my belief, though, that working together is the only way to make the types of gains that will address the inequities that have existed in America for generations. While there are varying views on the success of our national efforts, what is not in question is that our efforts provide ample opportunities for learning for future ecosystem work. My colleague, Tom Kane details some of those lessons in his article, Develop and Validate - Then Scale.

Admittedly, collaboration is not a new idea in the social sector. In a 2011 article that became the most downloaded in the history of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, John Kania and Mark Kramer proposed that large-scale change would require organizations to coordinate their efforts. Their framework for “collective impact” involves five conditions for collective success: a common agenda, shared measurement systems, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone support organizations. There is much overlap between the Education Ecosystem and the notion of collective impact. The Education Ecosystem extends and applies that model to a sector that is in many ways unique and therefore requires a framework of its own.

In applying the Education Ecosystem Framework personally, an educator considering a shift in her career trajectory might ask herself what impact she hopes to have and what problem - inequitable academic outcomes for students of color, comparatively low graduation rates for students with disabilities, the mismatch between what is taught in schools and what the workforce needs - she wants to solve. Then she should examine the root causes of that problem. Finally, she should analyze the roles each of the organization types represented in the framework play to help solve that problem and achieve that impact. Too many leaders try to tackle a problem without fully considering how that problem developed and how it gets perpetuated; effective leaders will aim to understand a problem from a 360-degree perspective to ensure that their solutions are appropriate.

Education Ecosystem Teams

What would it take to put into action the Education Ecosystem approach recommended here? One method is what I call Education Ecosystem Teams (EETs). An EET is a multidisciplinary team of diverse individuals working together to move the Education Ecosystem in the same direction. As an example, consider a group of master’s students at a higher education institution who see different paths to professional impact and who are brought together as part of an EET. Without guidance, some of these students might be inclined to focus singularly from their role or interests, whether school leadership, education policy, or otherwise. The Education Ecosystem Framework would certainly be useful to them as a career-advising tool, but I propose that it could also be a key piece of their training, enabling aspiring education leaders to enact the type of ecosystem thinking required to solve intractable challenges now and in the future.

In this example, graduate school students would work together in “learning pods,” as “learning technicians.” They would work on challenges submitted by communities around the country as they simultaneously respond to their local contexts. The benefits would be multifold: the students would extend their learning in an applied, field-based manner. The communities would benefit from the research and knowledge generated by the students at a time when budgets are tight. And, training institutions would deepen their impact in communities while providing a robust learning experience for students.

Conclusion

Three simultaneous crises are playing out in the United States today. COVID-19 has claimed more than 400,000 American lives. An economic downturn has cost millions of Americans their jobs. Rallies in response to the murders by white police officers of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor have taken place in communities throughout the country. Unprecedented demonstrations of people of all races, genders and ages are demanding reforms that enable everyone to not just survive, but also to thrive and to rise.

For many people, particularly people of color, these events made an already difficult situation worse. With a new administration shining a spotlight on all three national challenges, now is the time to think differently about how to reimagine what was normal and to begin to create something altogether better. A piecemeal approach will not suffice. I recently heard someone say, “How much we accomplish in this world depends on how much we can see.” During these volatile times in the United States - dare I say, the world - it seems particularly important to ensure that not only aspiring educators, but all of us are able to see new possibilities as well as new ways to make those possibilities a reality.

Because of the pain and suffering that occurred during this time, 2020 will go down as a year many will want to forget. Perhaps one way to pay tribute to the struggles and loss is by creating new opportunities for those who will be most vulnerable to future pandemics. Doing so will require us to rethink normal and embrace a framework where communities, policymakers, researchers, investors, and technical assistance providers work alongside and in sync with schools and communities for the betterment of students, teachers, and these very communities.

Author’s note:

One of the things that my parents taught their children as we were growing up was to, ‘Never forget the bridges that brought you over.’ I have had and continue to have many bridges who have supported me, even in the development of this idea. Shoutout to Vicki Phillips, Tom Kane and my Foundation Team for their support of the Gates Foundation work that I speak of in this piece. Also, shoutout to my HGSE faculty colleagues who gave me feedback on these ideas (i.e. Mary Grassa O’Neil and Ebony Bridwell-Mitchell, in particular). Also, special thank you to Matt Presser for his editorial and revision support.

About the Author:

Dr. Irvin Scott, a member of the Harvard Graduate School of Education faculty, teaches in the School Leadership Program and Doctor of Education Leadership Program and has launched and leads The Leaders’ Institute for Faith and Education (LIFE), which seeks to explore the intersection of faith and education in the lives of students and communities in a way that leads to better outcomes for America’s most vulnerable youth. Previously, Scott served as Deputy Director for K–12 Education at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, leading the investment of $300 million in initiatives focused on transforming teacher recruitment, development, and remuneration. Scott also led a team to initiate the Elevating and Celebrating Effective Teaching and Teachers experience, which has become a teacher-driven movement and can be found in a majority of states across the country (#ECET2). Prior to his Foundation work, Dr. Scott spent more than 20 years working as a teacher, principal, assistant superintendent, and chief academic officer including as Chief Academic Officer for Boston Public Schools. Scott holds a bachelor’s degree from Millersville University; a master’s degree in education from Temple University; and a master’s and doctoral degree from Harvard University.