As Boston Puts Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Center Stage, It Begins a New Conversation and A Reimagining of Itself

An Interview with Imari Paris Jeffries

Imari Paris Jeffries was named Executive Director of King Boston in June 2020. Paris Jeffries brings a wealth of experience from the non-profit management, racial equity, community activism, education reform, and social justice sectors, and has served in executive roles at Parenting Journey, Jumpstart, Boston Rising, and Friends of The Children. He serves as a Trustee of the UMass System and on the boards of United South End Settlement Houses, MA Budget and Policy Center, and Governor Baker’s Black Advisory Commission. Paris Jeffries is a military veteran, three-time graduate (B.A., M.Ed., M.A.) of UMass Boston, and currently pursuing his Ph.D. through UMass Boston’s Higher Education Program.

Mary Jo Meisner: Good afternoon, Imari. It's a pleasure to be here with you this afternoon to discuss King Boston and the role an initiative such as this one can play in the landscape of a city such as Boston and in the renewed national dialogue that our country needs to have on racial and economic justice.

King Boston began as an initiative to build a memorial to civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Boston Common, which is America's oldest public park with a 400-year-old history and tradition of civic gatherings. In its short life, King Boston has now grown into a project that also seeks to create a Center for Economic Justice that will serve as a catalyst for change through research and thought leadership, as well as an Embrace Ideas Festival of arts and culture events that will accompany the installation of the memorial. It is an ambitious, multi-faceted project in a city that has been plagued by a brand of racism since its school busing days of the 1970s.

It is particularly special to have this conversation during February, Black History Month, which creates an additional opportunity for all of us to reflect on the Black experience and contributions to our nation.

One aspect of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy and leadership is his own emphasis on developing and nurturing leaders of color. To kick off our interview this afternoon, I'd love to talk a bit with you about your background and what you brought to the helm of King Boston at this very momentous time of reckoning with racial justice issues.

It's been a pleasure to know you over the years, but tell our readers about your background, both personally and professionally, as a non-profit leader in Boston.

Imari Paris Jeffries: Mary Jo, it's been exciting to be a part of your life and have you a part of mine. I feel, as someone who came here from Tennessee when I was 18 years old to be stationed at Fort Devens, that at 47 I am a Bostonian. When my time was up in the service, I decided to stay in Boston and I've made it my home ever since 1991. I've had the opportunity to be nurtured by folks like you and others who have been instrumental in my journey and pathway as an up-and-coming community worker, then as an activist and non-profit leader, and now as executive director of King Boston. I've had an opportunity to combine national military service with service to my community; to work at several places that have filled my cup of knowledge around all the things that it's going to take for us to be a "beloved community," as Dr. King says. Having stints in early education and higher education and community organizing and philanthropy and board service, I am excited to bring all those experiences to King Boston. It's been a culmination of many folks who have invested in me, and my experiences in higher education, in the military and my love of our city, Boston.

MJM: Wonderful. Not to intimidate you, but taking on an organization called King Boston, it is quite something and congratulations to you. How do you see yourself carrying on Dr. King's legacy? In preparation for this, did you steep yourself in his works or has it always shaped your life or a combination of both?

IPJ: Dr. King has always been an important influence on me. As an undergraduate student, I was a Black Studies major and learning about King's life from an academic point of view, coupled with my cultural understanding of Dr. King as someone who grew up in the Black church down South. Dr. King's faith-based traditions were very much a part of my upbringing and I was able to combine that with my undergraduate studies of his philosophy. I've grown to understand how much of a genius Dr. King was. He was not only a man of faith, but he was also a scholar, and so his writings and philosophies expanded from civil rights to antiwar to workers' rights to the environment. He was a living, thinking Wikipedia of ideas, and I think a lot of that perspective has influenced me as a community activist and a non-profit leader. You know our friend Robert Lewis Jr. (founder of The Base athlete-scholar non-profit in Boston) talks about five tools that baseball players use -- pitching, running, fielding, hitting and throwing. I think that perspective also translates to leadership. Leaders need to be able to speak and inspire. We need to be thoughtful about what we're talking about. We need to have a genuine love for community and people and we also need to understand that there's power in writing and policy. And so I have evolved in my own growth as a non-profit leader. I've developed new tools and these were tools that Dr. King had at an early age. Many of us forget that he was assassinated when he was 39 and was already a national figure in his 20s, so it's a lot to aspire to.

Those are huge shoes that I don't think I could ever fill, but it is great to have his spirit embodied in a lot of leaders that are relevant in Boston today. There are so many who are embodying the spirit of Dr. King that I get to be a part of. So I'm super excited about that.

MJM: Thank you for reminding us that Dr. King was only in his 30s when he was assassinated. It is really just profound to think about that and to think about his leadership journey and how much more it could have been, about how much more he could have contributed.

The King Boston initiative, interestingly, was founded by a white tech entrepreneur in Boston, Paul English, who many of us knew at that point as the founder of a travel booking site kayak.com, which he sold to PriceLine for $1.8 billion in 2012. And after that he has devoted himself to this journey and boldly envisioned the idea of designing and building the first new memorial on the iconic Boston Common in decades. So tell us about King Boston, starting with the idea of the monument that is called The Embrace.

IPJ: From what I understand, the idea of a King memorial in Boston happened when Paul visited a King memorial in San Francisco. It's fitting that a founder of a travel website would be the founder of King Boston because when one thinks about traveling, one thinks about exploring and imagining and experiencing many worlds and having those become a part of one's experience. Dr. King imagined a world that was different from the one that he lived in.

In 2016, when Paul started this initiative it initially was to honor Dr. King. But it evolved to also honor Mrs. King and Boston civil rights leaders. And it was decided that this memorial would be located in the Boston Common, America's oldest public park -- a space that hadn't had any new sculptures in the last 28 years. There was a moratorium on building anything new there. I think it is important for us to think about what it means to put a symbol in Boston's financial heart -- the place that so many visitors traverse every year -- to represent the values that the city aspired to. The memorial part of it was always important, but we understood as the initiative progressed that it also was important in a city like Boston for us to do more than just place a memorial on the Common. We also needed to understand the significance that Dr. King had in Roxbury (a primarily Black neighborhood of Boston) and the 12th Baptist Church. That was Dr. King's home church when he lived in Boston, and where he met (his future wife) Coretta. The Rev. Dr. Michael Haynes (pastor of 12th Baptist when Dr. King was a member) was an important figure and friend of Dr. King's, and so we wanted to have a King Center for Economic Justice be located in Roxbury, as a representation of these two points on the map of Boston -- its Financial Center on the Boston Common and the heart of Black Boston in Roxbury.

And it's also very important that as we experience the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd that the King Boston organization continues to evolve as the country is wrestling with what it means for monuments and memorials to be a part of a cityscape. We saw cities like New Orleans decide to take down monuments to the Confederacy. We saw cities like Richmond interrogate what it means for Monument Row to be so prominently displayed in that city and we saw them rethink those monuments to the Confederacy. Even in our home city of Boston, we saw the beheading of the Christopher Columbus statue in the North End and difficult conversations around the Emancipation statue in Park Square (which portrayed Abraham Lincoln standing over a newly emancipated Black man, and was removed late last year).

We understand that monuments and memorials have to represent values. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (a white Southern women's "heritage" group founded in 1894) built more than 700 monuments honoring the Confederacy decades after the Civil War that they lost. More than 400 were built between1920 to modern-day. They are markers of fear and intimidation. And so what does it mean in this environment where we are having this racial reckoning for a monument to represent a city and what do we want that monument to represent? This idea of Embrace Ideas Festival emerged from that because there has to be different ways to engage in conversations around these things. So there is a policy/research/grassroots organizing way that the King Center will represent and there's a humanities/arts and culture way which Embrace Ideas will represent.

MJM: I'm going to ask you to tell us a bit more about those two King Boston initiatives in just a minute, but first I'd like you to remind us about the history that Dr. King and his wife Coretta have in Boston because many people don't often think of Boston when they think of the Kings. The first city people probably think of is Atlanta. What did the Kings do here? What brought them here? And why is the Boston Common such a perfect place for this memorial called The Embrace?

IPJ: That's right. So they met here as college students. Dr. King was at Boston University and Mrs. King was a student at the New England Conservatory in the 50s. And one of the other things that I think people also may not know is that Boston is the fourth largest college town in the country and the ninth largest city in the country and so the Kings were a part of this wave of college students that came to New England to go to school. Rumor has it that their first date was in the Public Garden, near the Frog Pond, and that on that date Dr. King asked Mrs. King to marry him. I can imagine, having heard Dr. King's speeches, how smooth he must have been on a first date to ask someone to marry him! And it certainly worked out for them. And so, you know their love story originated in our city, and there's an alternative universe where Boston was not the city of our unfortunate reputation as a racist city, but one that was a welcoming city that was racially just. The Kings stayed after they graduated from college and in some ways Boston may have been an epicenter of the national civil rights movement. And so 56 years later, we have that chance to do it again. We're revisiting this moment in time. And so we have an opportunity, post-pandemic, to imagine Boston as the epicenter for anti-racist movement today.

MJM: So digging a little bit further into that history, Dr. King gave a sermon on Boston Common in 1965. And, of course, he has given so many more that have served as a call to action in the pursuit for justice, including the Drum Major Instinct sermon.

IPJ: The Drum Major Instinct sermon was one that a lot of us have cut our teeth on, in AmeriCorps national service and others. There's a line from that sermon that goes "Everyone can lead because everyone can serve." The AmeriCorps national service movement, the Points of Light Foundation that George H.W. Bush founded, and embraced by Bill Clinton, then George W. Bush. I think that everyone can lead because everyone can serve. It was a call to action for us, reimagining what it meant for us to be citizen volunteers for our country. And that's why that sermon is so familiar to us. And when I think about its relevance to us today, I think we have a real opportunity. We've been sheltered at home during the pandemic. What does it mean for us to step into our citizenship, as a sense of belonging to a community? I think that is one of the biggest things that I've taken from that sermon is how do you be a part of something that is inclusive, for everyone to contribute to use our values and create the New Boston, the New Cambridge, the New Region. I've learned so much about so many of King's sermons. If there is a topic that you're interested in, Dr. King has written about it in some amazing ways. And so, yes, the Drum Major Instinct sermon is one of my favorites. It's a direct throughput to another pillar of the work that you're doing, which is the creation of this Center for Economic Justice and using it in a way to really highlight and activate new ways that the sermons and the speeches that Dr. King gave and ground them in a new current reality. I think in this time we have to interrogate and think of new solutions to become a society like we would trying to find a cure for cancer. I think a lot of the literature that is from the New York Times’ 1619 Project and Dr. Ibram X. Kendi's book "How to Be an Antiracist" really talks about how we've been socialized into this culture.

And so I don't believe that we're going to find a solution doing the same old things in a different way. I think we have to experiment with new ways and interrogate the old ways and ask ourselves -- do these ways still serve us as a society?

MJM: I'm excited about what that means for us as a city. Do you see your Center for Economic Justice doing original research and putting forward new ideas and solutions?

IPJ: I think they'll definitely be a role for some original research, but I think one of the things that makes Boston so special is that we are so resource-rich and we don't do as good a job all the time of coordinating our rich set of resources. And so I see our role as being a bridge builder on research and filling the gaps. I also see our capacity as a convener and holding space for all the amazing higher education and research institutions that are in the Commonwealth. I think there's a role for what I refer to as community note taking. You know how when you go to a meeting and you say "who's going to take the notes" and everyone looks down and someone finally says, "okay, I'll take the notes" and you're like "Phew," and you're glad that they took those notes because you now have archived the meeting and set up a project plan of what happens next and have built a sense of accountability of what was discussed. And so there's a role for King Boston to serve as the community note taker, because we have so many resources in this city and there is a need for us to coordinate those resources. I think there's a unique role for us there.

MJM: Similarly, you've imagined an annual festival of ideas in arts and culture as part of King Boston. All of these things taken together are quite a different and important statement being made in Boston, a city that has had a difficult history of race relations.

I'm part of an initiative where we're trying to create a new narrative, a branding narrative about the city, because we know that people on the outside -- and frankly, inside -- see us in a way that we don't believe we entirely are anymore. So can you talk a bit about the festival and the larger meaning of King Boston in terms of helping rebrand our city and to talk about the racial diversity that exists here and what it means.

IPJ: You know in that same Drum Major Instinct sermon, King starts off by talking about two Apostles, James and John, asking Jesus "Could they sit in?" They could bask in the glory of being on Jesus' left and right-hand sides. And so, throughout the sermon, King ultimately transitions to talking about service isn't about this sole glory; it is about service through how we give to others. In this time in which we are building the first memorial in Boston Common in 30 years, this could undoubtedly be a King Boston moment. This could certainly be when some of the actors of King Boston could be champions for creating a new sermon. But what would that really mean, in the spirit of Dr. King, to be on the right and the left-hand side and be in service, be a bigger moment for all of us for all of Bostonians? Could Dr. King's values challenge us? Can we make this a catalytic moment for Boston? Can we use it as the impetus to have these conversations? Can we look at it as a way to say Boston recognizes that we had a reputation that looked like this and now this memorial is a symbol of hope? To say that we've come out of the pandemic a lot different, a lot more empathetic, a lot more loving, a lot more caring. I think this memorial allows all of us to take pride. It just doesn't belong to King Boston or the Boston Foundation. It belongs to all of us in the Commonwealth. And so what could we do to open Boston up in a major way? Could we utilize our unveiling of The Embrace and talk about using public and private vending dollars to stand up Black and brown businesses who have struggled during the pandemic, for instance? So right now, there are about 30 organizations that have committed to hosting events during this festival. That's the "beloved community" that's worth building a memorial for and that's where Embrace Ideas Festival comes from. It's about us utilizing moments that benefit all of us all the time and not just basking in the right and the left-hand side of glory, but looking at this as an opportunity to serve. We're talking about launching it in October of this year to start that festival, and then the monument being built and then being unveiled in 2022. It's going to take 17 months to fabricate the bronze Embrace statue. So we are starting the Embrace Ideas events now as virtual and hopefully live events, and then in October 2022 it will be the full-fledged Ideas Festival with the unveiling of The Embrace.

MJM: Do you see the initiative playing a similar role on the national stage? We've just gone through a brutal year in our country, with the George Floyd murder and all the other racial tragedies in our country. Is there a role for King Boston on that front?

IPJ: I think so. Part of it is, we know that the NAACP conference is coming in 2023 and our Embrace Festival will be started in 2022. We think that there are a lot of national prominent leaders who are in Boston who have been engaged in these issues and it's important to elevate those leaders into a national platform.

Some have argued that Rev. William Barber, who is President and Co-chair of the Poor People's Campaign and the NAACP head in North Carolina, has talked about this third reconstruction that we're in the midst of right now. The other two reconstructions were the first one that happened right after the Civil War and the second one that occurred between 1948 and in the late-60s and that started when black GIs returned from World War II, all the way up into the Civil Rights movement. Some argue that this is the third reconstruction. Reconstructions are made up of three elements -- political, economic, and social. I think Bostonians read the (Boston Globe's) Spotlight series (on race relations in Boston) a few years ago and we got angry and we got frustrated. There are people doing things that we didn't like, that we didn't think represented us. I think Bostonians and folks in the Commonwealth took all that seriously, and I think we've seen the emergence of lots of Black and brown and other leaders over the last several years. In Boston, we are on the verge of the first Black woman mayor; our city council is made up of mostly women. The major heads of police here and in Cambridge were all men of color, as well as the District Attorney in Suffolk County as a black woman and (black Congresswoman) Ayanna Presley unseating an incumbent and growing in stature on the national stage. This is a part of this third reconstruction. We're also having conversations around economics for all of us and social justice as well. What does it mean to be a city that is welcoming? What does it mean for us to thrive in the Commonwealth? And I think that is a part of this reconstruction story that Boston is going through at this moment in time and a role for King Boston to play.

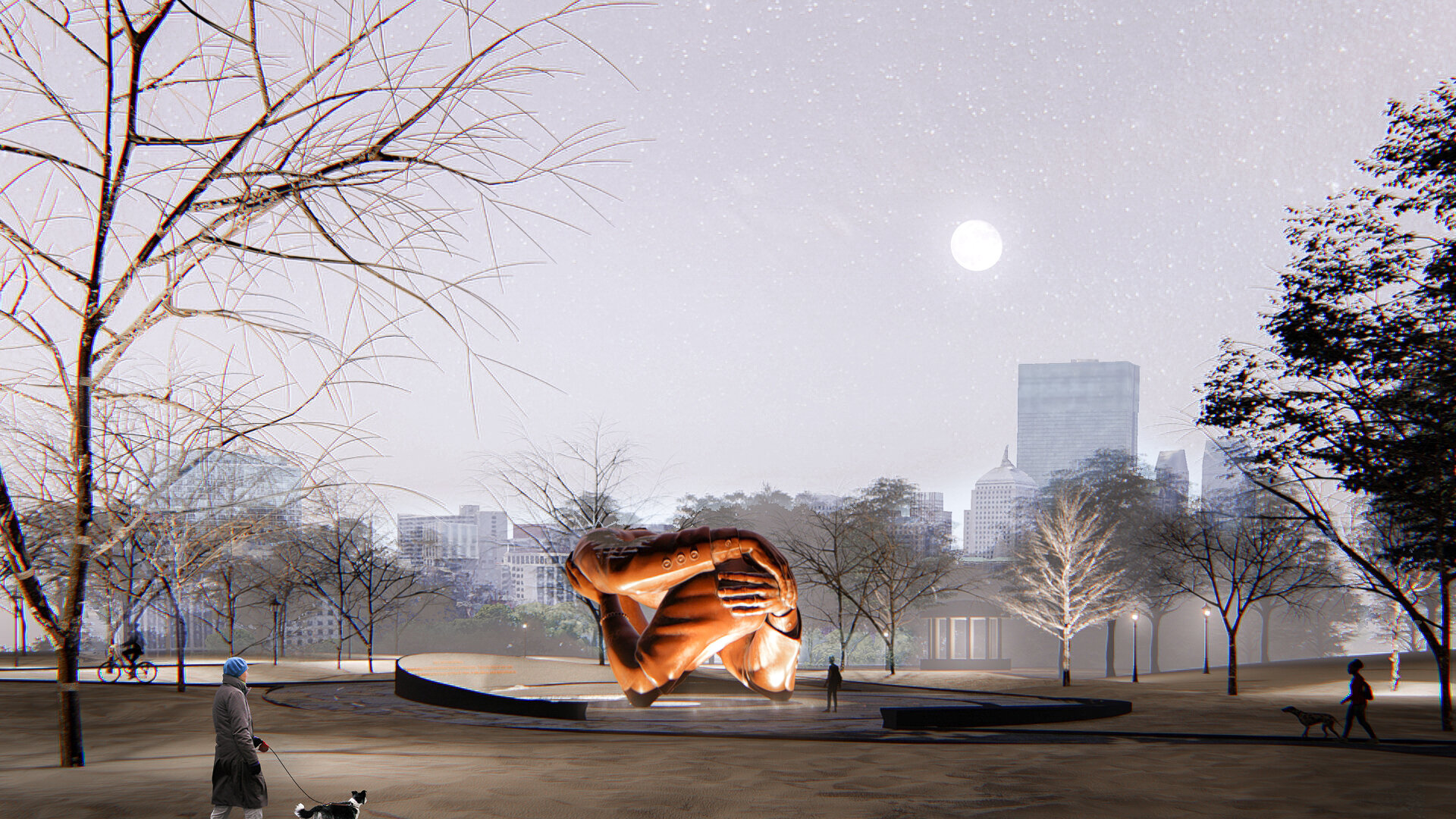

The Embrace

Credit: Designed by Hank Willis Thomas and MASS Design Group

About the Author:

Mary Jo Meisner is a senior business executive specializing in communications, media, government relations, and public policy. Over the course of a 30-year career, Mary Jo has been a journalist, a newspaper and business executive, and was the architect of a groundbreaking civic leadership arm of the Boston Foundation. After spending a year as a 2017 Advanced Leadership Initiative fellow at Harvard University, Mary Jo formed MJM Advisory Services, a bespoke consulting firm that advises senior leaders in the private sector on their social impact initiatives.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.